2 Sep 2010, Silver Spring, Maryland, United States…Ansel Oliver/ANN

Lisa Beardsley wants to create value for the education consumer.

In business school she analyzed why people chose to pay $4 for a cup of coffee at Starbucks. She now takes that same analysis and applies it to Adventist education, examining why spenders would offer a premium for its values and mission.

For Beardsley, the recently-appointed Education director for the Seventh-day Adventist world church, that analysis and its subsequent results, she hopes, will offer administrators and students clearer choices to navigate change in Adventist education. The system struggles to maintain Adventist identity in areas of surging growth and offer competitive programs in stagnating regions.

The typical college student is no longer just an 18-year-old coming to live in the dorm. Demand is increasing for graduate and professional degrees. Parents are returning to school, sometimes in downtown extension buildings or via online classrooms. The challenge, Beardsley says, is how to make each of those points in the delivery of the academic experience, whether rural or urban, distinctly Adventist. This updates the old business model of building Adventist boarding schools and colleges at the end of rural roads.

Much of that analysis will need to take place over the course of her department’s five-year term. She and four associates comprise the core of the Adventist Accrediting Association.

Where’s the growth?

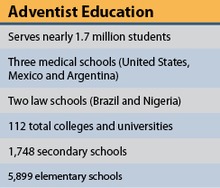

For now, analysis of 1.7 millions students in Adventist education worldwide reveals their preferences by their tuition payments and attendance. The results: The church’s education system is growing fast, mainly outside of North America.

While growth exists in the United States and Canada, Beardsley says enrollment in Adventist higher education only grew there about 3 percent over the past five years. Long established denominational infrastructure is waning in a few areas. Education leaders in North America say many academies built in the early 1960s to accommodate Baby Boomers are down in attendance from their prime. Beardsley points out that most colleges are strong, but changing demographics and market demand mean once flourishing schools should scale back operations, a few more radically.

Take Atlantic Union College in Massachusetts, which is on the verge of losing accreditation for financial reasons. It could perhaps re-emerge successfully as a junior college, Beardsley says, referring to the nation’s “booming” demand for community colleges.

“If people aren’t able to pay or aren’t willing to pay, and if [certain areas] close up, we should prayerfully consider what the Lord would have us do,” Beardsley says during an interview in her office. “There are other places where we can’t manage the growth. I don’t think we should keep other things on life support.”

Worldwide, however, higher Adventist education is growing so fast — about a 26-percent enrollment increase over the past five years — that more and more teachers are hired who aren’t Adventist. Increasingly, they’re teaching students who aren’t Adventist either.

Granted, when 40 percent of students aren’t Adventist, it’s an opportunity to share the church’s mission. But what defines Adventist education, Beardsley says, is who’s teaching the class.

That’s why one of her goals over the course of her term is to empower teachers to continue integrating faith with learning and increase the percentage of professors who are members of the denomination.

“All of our teachers, even those teaching in an MBA program at night, need to understand how they can further redemptive purposes in their instruction,” Beardsley says.

Additionally, she wants to increase spirituality on Adventist campuses, which emphasizes a balance of study, work, service and rest. That might include somehow boosting the influence of religion and theology departments on campus. The programs are shrinking relative to other disciplines in response to market demand and now have less of an influence on a campus culture, Beardsley says.

“We need those teachers to exert leadership and influence not just for their students, but for the intellectual and spiritual climate of the entire campus,” she says.

Although she seeks to increase Adventist identity and spirituality on denominational campuses, Beardsley isn’t opposed to exposing students to a variety of ideas and evidence, even when in conflict with official Adventist beliefs.

“It needs to be done, but in balance with Adventist identity and mission,” she says. “It needs to be done in appropriate context at the right time and with sufficient support for students as they wrestle through intellectual issues, such as what is the current scientific thinking about the age of the earth, and how do we reconcile that with our belief that God is our creator.”

Still, she cautions that such topics should be taught with “maturity, judiciousness and mindfulness.”

“There are things that academics talk about among themselves with other professors and there are things they talk about with undergraduates. And it’s not the same thing. …We should never throw our students to the wolves and let it be survival of the fittest.”

Calling to ministry

Beardsley, 52, is fluent in English and Finnish (she’s half Finnish and half Japanese) and a longtime professor and student in Adventist and public schools around the world.

She took the theology track in college in Europe, not realizing until her junior year that a woman couldn’t serve as an Adventist minister. When asked about it, she says she was “shocked” at the time, but that her calling now is through the ministry of education.

Still, she put that theology training to use during two stints as a hospital chaplain between teaching and pursuing academic degrees, which now form the alphabet soup following her name — Ph.D., MBA, MPH.

Her four degrees — in education, business, health and theology — make up the four largest disciplines now on Adventist campuses.

Reaching students

Most recently, Beardsley served as a department associate director and editor-in-chief of Dialogue, a journal geared toward Adventist students on public campuses. That’s where roughly 70 percent of Adventist college students in North America study. And she’d like to have more of them in Adventist schools.

Wouldn’t that crowd existing campuses? Not outside North America, she says.

Her own career has more or less been aided by a rotation of schools and developing connections — “social capital,” she calls it. Today, e-mails to executives in Indonesia or Pakistan aren’t misinterpreted because of culture. Familiarity and trust was built on campuses decades ago. The denomination functions on that capital, she says.

“I tell students, ‘Don’t just think of the school closest to you. Think of the world.’ My own experience — two years in England, two years in the Philippines, a year and a half at Loma Linda — gave me an understanding of the world I could not have gained any other way.”

–write her at beardsleyL@gc.adventist.org